Accountability is at the heart of nonprofit accounting. Because your organization can’t turn a profit by definition, the goal of tracking your finances is to demonstrate to donors, funders, the government, and the community that you’re using your funding responsibly to further your mission.

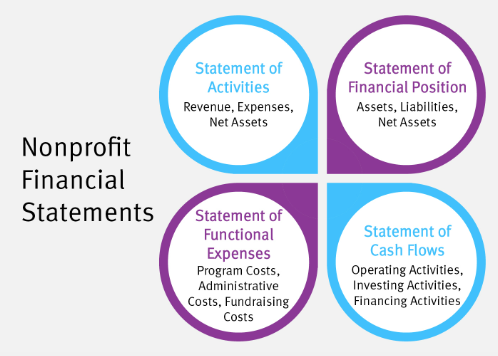

Financial reporting is critical for accountability, and financial statements are among the most important reports your nonprofit will create each year. Each of these documents organizes and summarizes your organization’s financial data in a different, actionable way to promote improved internal decision-making and external transparency.

In this guide, we’ll walk through the information included in each of the four core nonprofit financial statements and the main insights you can glean from each one. Let’s get started!

1. Statement of Activities

The statement of activities is the nonprofit equivalent of a for-profit income statement. It provides detailed information about your organization’s transactions during a given year, showing where your funding came from and where it went as you furthered your mission.

Each nonprofit financial statement is divided into three sections. For the statement of activities, the three parts are:

- Revenue. This section details your organization’s major funding sources and the total amount you brought in from each one throughout the year. It’s helpful to organize this section according to the five primary categories of nonprofit revenue—individual donations, corporate philanthropy, earned income, investments, and grants—to align with your budget and internal records.

- Expenses. This section breaks down all of your nonprofit’s annual expenditures, categorized by function: program, administrative, and fundraising. We’ll dive deeper into these functional expense categories later, but program costs are directly related to your mission, while administrative and fundraising costs together make up your nonprofit’s overhead.

- Net assets. To calculate your organization’s net assets (i.e., total worth) at the end of the year, subtract your total expenses from your total revenue. Many nonprofits include their net assets from the beginning of the year in the statement to see how this number has changed over time. It’s also useful to separate unrestricted and restricted net assets so you know what funding you’re free to spend and how much is already designated for specific activities.

To promote external transparency, use your statement of activities to fill out your nonprofit’s annual tax return and create the financial charts and graphs in its annual report. Internally, this report is most useful for budgeting. When the line items in your statement of activities match your operating budget, you can make more educated, data-driven projections about the coming fiscal year’s revenue and expenses.

2. Statement of Financial Position

Also known as a balance sheet, the statement of financial position provides a snapshot of your organization’s financial health. While the statement of activities focuses on short-term spending and revenue generation, your balance sheet is more concerned with long-term financial commitments.

The three sections of the statement of financial position are:

- Assets. These include everything your nonprofit owns, such as cash, accounts receivable, investments, property, and equipment. You’ll typically list these in order of liquidity (i.e., spendability)—cash goes first because it’s already liquid, and property and equipment go last because you’d have to sell them for them to become liquid.

- Liabilities. This section details what your nonprofit owes, including lines of credit, loans, and accounts payable. These appear on the statement in order of payment due date, with short-term investments listed above long-term liabilities.

- Net assets. On your balance sheet, you’ll calculate your nonprofit’s net assets by subtracting your total liabilities from your total assets. The number will differ from your statement of activities because this calculation includes short- and long-term fiscal considerations. However, you should still separate net assets with and without restrictions.

This report shows how much flexibility you have to fund future growth, as well as your readiness for unexpected challenges. Infinite Giving’s nonprofit cash management guide recommends keeping at least six months of cash reserves on hand in case of emergency or to keep your organization running as you invest in expansion. Your statement of financial position can tell you whether you have enough money in reserve, what investments you may need to make, and if you have assets you could liquidate to reach your goal.

3. Statement of Cash Flows

The statement of cash flows is just what it sounds like: a report showing how cash moves in and out of your organization. According to Jitasa, most nonprofits pull cash flow reports monthly rather than annually to keep a better handle on this movement throughout the year.

The statement of cash flows describes cash movement from three types of activities:

- Operating activities: Spending and revenue generation from your nonprofit’s day-to-day operations. Cash inflows from operating activities include monetary contributions from individuals and corporations, most grants, and earned income. Cash outflows from operating activities include most program expenses and variable overhead costs.

- Investing activities: Cash movement related to long-term assets. Cash inflows from investing activities may include putting reserve funds in new investment vehicles and buying or improving fixed assets like property and equipment. Cash outflows from investing activities include investment returns and proceeds from sales of fixed assets.

- Financing activities: Cash movement related to your organization’s capital structure, most of which concerns incurring or paying off debt. Building a nonprofit endowment fund is also a cash inflow from financing activities, although generating and using interest from these funds are considered investing activities.

This statement helps you develop stronger fundraising plans and critically evaluate your nonprofit’s spending habits to make adjustments in real time. Monthly cash flow reports also show when your nonprofit raises and spends the most during the year (for example, charitable giving tends to peak at year-end and die down in the summer) so you can plan accordingly.

4. Statement of Functional Expenses

The statement of functional expenses is the one financial statement unique to nonprofits because it shows how your organization’s expenses further its mission. It’s laid out as a table or matrix, with various types of payments (natural expenses) on one axis and the three aforementioned categories of functional expenses on the other.

Here are some examples of natural costs that fall into each functional expense category in this report:

- Program costs: Vary widely according to your organization’s mission—e.g., purchasing pet food and veterinary care for an animal shelter, buying beach cleanup supplies for an environmental organization, or paying for exhibition setup and maintenance at a museum

- Administrative costs: Staff compensation, utility bills, rent or mortgage payments, office equipment purchases, insurance

- Fundraising costs: Fundraising consultant fees, fundraising software purchases, marketing material creation, branded merchandise production, event planning

Like the statement of activities, the statement of functional expenses is useful for tax filing, annual report creation, and budgeting. In particular, if you need to cut costs in your upcoming operating budget, understanding your functional expenses will help you find reasonable ways to reduce overhead spending before taking any funding away from your programs.

Each of the four core nonprofit financial statements plays an important role in your organization’s accounting processes—and, therefore, in its ability to further its mission. To increase external transparency even more, consider making your financial statements available on your nonprofit’s website or attaching them as appendices to your annual report so interested stakeholders can easily learn more.ritically evaluate your nonprofit’s spending habits to make adjustments in real time. Monthly cash flow reports also show when your nonprofit raises and spends the most during the year (for example, charitable giving tends to peak at year-end and die down in the summer) so you can plan accordingly.

4. Statement of Functional Expenses

The statement of functional expenses is the one financial statement unique to nonprofits because it shows how your organization’s expenses further its mission. It’s laid out as a table or matrix, with various types of payments (natural expenses) on one axis and the three aforementioned categories of functional expenses on the other.

Here are some examples of natural costs that fall into each functional expense category in this report:

- Program costs: Vary widely according to your organization’s mission—e.g., purchasing pet food and veterinary care for an animal shelter, buying beach cleanup supplies for an environmental organization, or paying for exhibition setup and maintenance at a museum

- Administrative costs: Staff compensation, utility bills, rent or mortgage payments, office equipment purchases, insurance

- Fundraising costs: Fundraising consultant fees, fundraising software purchases, marketing material creation, branded merchandise production, event planning

Like the statement of activities, the statement of functional expenses is useful for tax filing, annual report creation, and budgeting. In particular, if you need to cut costs in your upcoming operating budget, understanding your functional expenses will help you find reasonable ways to reduce overhead spending before taking any funding away from your programs.

Each of the four core nonprofit financial statements plays an important role in your organization’s accounting processes—and, therefore, in its ability to further its mission. To increase external transparency even more, consider making your financial statements available on your nonprofit’s website or attaching them as appendices to your annual report so interested stakeholders can easily learn more.

I can’t wait to meet with you personally.

I can’t wait to meet with you personally.

Comments on this entry are closed.